Paper: Eight New Milky Way Companions Discovered in First-Year Dark Energy Survey Data

This paper is about the discovery of eight new Milky Way satellite galaxy candidates found in the first season of DES data. We call these objects galaxy “candidates”: we’ve found strong evidence for their existence through the information that DES provides (colors and brightnesses of stars), but observations with other telescopes are required to be certain they are indeed galaxies.

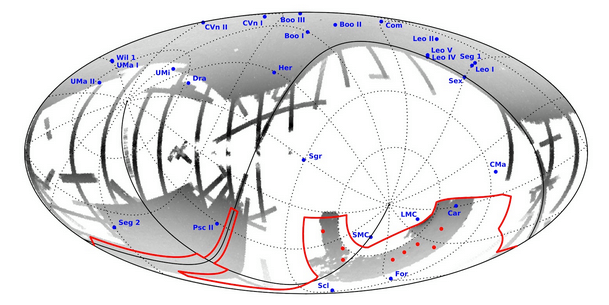

Our Milky Way galaxy is surrounded by an unknown number of smaller “satellite” galaxies. About two dozen of them have been discovered—many of them years ago, with the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS; www.sdss.org). A satellite galaxy can span a region of the sky as large as 1/5th the size of the full moon, but still be so faint as to be undetectable to all but the most sensitive telescopes. Satellite galaxies range in physical size from tens to hundreds of light-years across. Some reside just beyond the edge of the Milky Way disk, and some are 20 times farther away—almost half a million light-years from us. For comparison, the Sun’s nearest neighboring star, Proxima Centauri, is about four light-years away.

All galaxies, including our Milky Way, contain more dark matter than light-emitting matter. That’s even more true for dwarf galaxies, which are even more highly dominated by dark matter. We know this because satellite galaxies are a thousand to a million times dimmer than our Milky Way, but only a hundred times less massive. All that extra mass comes from non-visible dark matter, and as such, these galaxies may prove critical in helping us understand the nature of this mysterious substance.

Milky Way satellite galaxies are so faint that they can only be found by looking at the individual member stars that comprise them. There was an explosion of discovery 10 years ago with the start of SDSS, which turned into a trickle and dried up completely 5 years ago. Our search for new Milky Way satellite galaxies uses the first-year DES data covering about 1,800 square degrees of sky area (about 1/20th of the whole night sky).

One challenging element in the search for satellite galaxies is that we must differentiate between the stars belonging to the satellite galaxy and those that are actually in the Milky Way itself. We overcome this challenge by finding objects that are not only clumped in space, but that also follow a pattern in their colors. Moreover, we can use the fact that there should be very few heavy elements, like iron, in these very old galaxies (between 10 and 13 billion years in age): over time there has not been enough stellar activity to eat hydrogen and then spew out heavier elements from the stellar life cycle process.

The last step in the process to confirming our satellite galaxy candidates is to obtain spectroscopic information, which will tell us if these groups of stars and gas are gravitationally bound in and of themselves, like other galaxies.

The DES provides us with the first opportunity to see this part of the sky to such depth and in so much detail. The newly discovered satellite galaxy candidates increased nine-fold the number of known satellites in the southern hemisphere. These objects are close to the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, suggesting that there may be a complicated history between the Milky Way and its largest local neighbors. These objects were also independently discovered by a group of researchers at Cambridge University using the public DES images (http://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02584).

Since this result came from only the first year of DES data, we expect more exciting things to come.

About the Authors: Keith Bechtol and Alex Drlica-Wagner

Keith is a Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics (KICP) fellow at the University of Chicago. His research interests are focused on the physics of satellite/dwarf galaxies, cosmic neutrinos and high-energy cosmic rays. In his spare time, he runs … a lot—enough to win the San Francisco marathon. Keith has been at KICP since 2012.

Alex is a Schramm fellow at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (FNAL) in Batavia, Illinois. His research interests are focused on satellite/dwarf galaxies, dark matter and gamma rays. In his spare time, he throws disk with the Chicago Wildfire (http://chicago-wildfire.com/). Alex has been at FNAL since 2013.