Astronomers know many facts about galaxies. For example, we know that their colours tell us about the stars inside them and how old they are. We also know that their shapes can tell us about how they formed. Past and current large-scale surveys such as the Dark Energy Survey (DES) observe millions of galaxies at different distances, and therefore at different stages of their evolution. These galaxies can be catalogued and characterized in a number of different ways. However, one type of star system we know little about are binary neutron stars (BNS). The handful of confirmed binary neutron stars found have all been within our own galaxy.

The optical counterpart to GW170817 was observed by the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) and other instruments to have come from a galaxy named NGC 4993, which is 130 million light years away from us. This event was likely produced by a binary neutron star merger. Antonella Palmese, together with other galaxy evolution and gravitational wave experts (Will Hartley, Marcelle Soares-Santos, Jim Annis, Huan Lin, Christopher Conselice, Federica Tarsitano and more) asked the question: what can we learn about the stars in NGC 4993? How did this binary system emerge in the overall history of the galaxy? Although we only have one snapshot of this galaxy, which is precisely 130 million years old, we can make use of other properties to infer how this galaxy evolved over cosmic time.

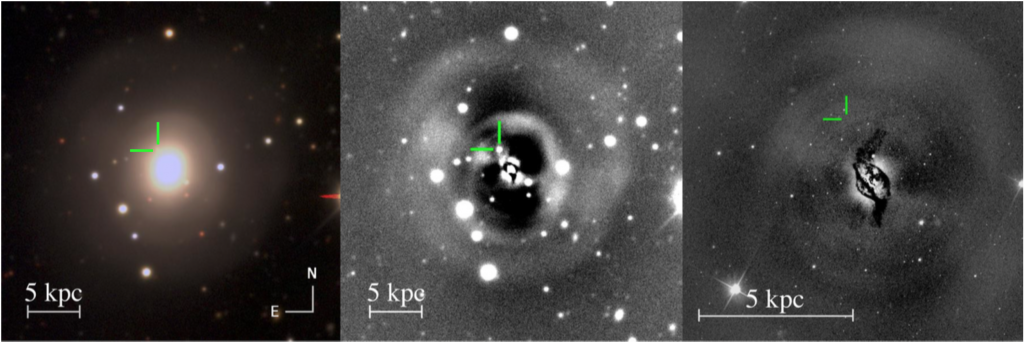

At first glance, NGC 4993 looks like a normal, old massive elliptical galaxy (left panel in Figure 1), known by astronomers as an “early type galaxy”. But if we examine it more closely, we see that it contains shell structures: arcs of brighter stellar densities around the center of the galaxy. If we consider the profile of a typical, early type galaxy (see middle panel in Figure 1) and subtract it from the profile of NGC 4993, we notice key differences that help us characterize the kind of environment needed for binary neutron stars to form.

Figure 1. Left panel: DECam image of NCG 4993. Shell structures indicative of a recent galaxy merger are clearly visible. Middle panel: r-band residuals after subtraction of a Sérsic light profile. Right panel: F606W-band HST ACS image with a 3 component galaxy model subtracted. Dust lanes crossing the centre of the galaxy are evident after this subtraction. The green lines show the position of the transient.

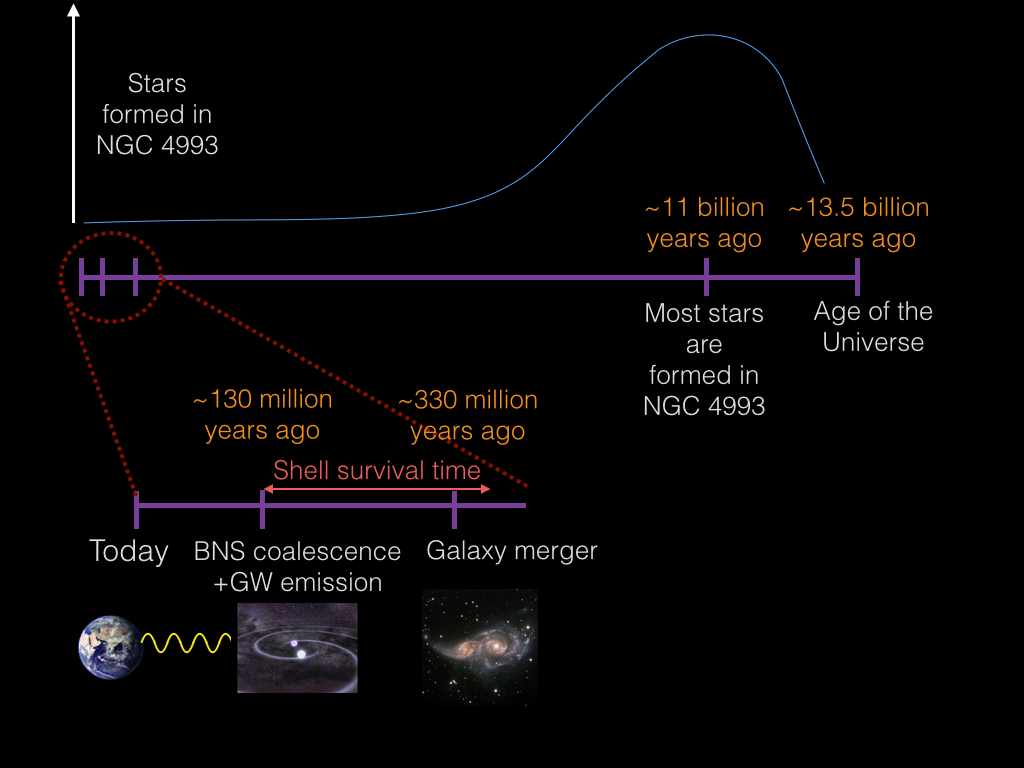

A number of papers starting from the 1980s have supported, with simulations and observations, the idea that these kind of shell structures are the debris of a recent merger between two galaxies (see a simulation example: http://hubblesite.org/video/558/news/4-galaxies ). During the merger, the stars from the smaller galaxy that passed close to NGC4993 millions of years ago were stripped away. As a result, many stars are concentrated in these arc-like regions. From the innermost shell position and the velocity of stars, we estimate that the shells in this galaxy should be visible for ~200 million years before dispersing. This means, if we still see them, the galaxy merger must have happened up to 200 million years before the BNS coalescence (see Figure 2 for a timeline). Could the dynamics of this galaxy merger be involved in the formation of the GW progenitor?

Figure 2. Timeline of NGC 4993

DES only observes in optical photometric bands so we added information from infrared and spectroscopic surveys to study this galaxy in greater detail. We find more evidence for a recent galaxy merger (e.g. dust lanes, right panel of Figure 1, and two different stellar populations). We also find that the age of most of the stars in this galaxy is ~11 billion years old – only a few billion years younger than the Universe! This means that during its ‘recent’ stages, this galaxy has not been forming stars.

Most of the current models for the formation of BNS suggest that they begin as a binary of two massive stars from a star formation event. During the evolution of the massive star binary, both stars will become supernova. If the gravitational force between the stars is strong enough to keep them bound against the force of the supernovae explosions, they become neutron stars in orbit until they coalesce. Simulations show us that neutron stars usually orbit around each other for ~500 million years before they merge, but it can take up to some billion years. Their lifetime before becoming neutron stars is much shorter than that.

So if there was no recent star formation in NGC 4993, where did these massive stars, which go on to become neutron stars, come from? If they formed 11 billion years ago with other stars in the galaxy, why did they only merge now? Our work shows that it is unlikely that the BNS was formed ordinarily. We do not expect this BNS to be so old given the current knowledge of their expected lifetime from simulations. We instead suggest that the formation of the BNS was not through traditional channels. Instead, dynamical interactions between stars due to the galaxy merger might have caused the two neutron stars to form a binary or to coalesce. The plan for the future is to discover many more of these BNS systems inside their galactic hosts. With more data, it will be possible to determine how galaxies are able to produce the right conditions for this energetic dance of dense bodies to occur, creating ripples of energy (gravitational waves) that teach us about the Universe.

About the Author & Editors

Author: Antonella Palmese

Antonella is a PhD student at University College London. Before moving to London, she graduated in Physics (BSc) and in Astronomy and Astrophysics (Masters) atLa Sapienza University of Rome. While her studies focus on theoretical cosmology, at the moment she is focusing on observational astrophysics with DES. Her main interest is studying stellar masses of galaxies, and she has also been involved in the estimation of their redshift. She also works on gravitational redshifts in galaxy clusters.

This DArchive is based on Antonella’s paper available here.

Editors: Sunayana Bhargava & Ross Cawthon

Sunayana is a PhD candidate at the University of Sussex working under the supervision of Kathy Romer. Her research interests involve using clusters of galaxies as cosmological probes, combining X-ray and optical data.

Ross is an astrophysics PhD candidate at the University of Chicago. He works on various projects studying the large scale structure of the Universe using the millions of galaxies DES observes. These projects include galaxy clustering, correlations of structure with the cosmic microwave background, and using the structure of the Universe to infer redshifts of galaxies. Ross is also an active science communicator, volunteering at Chicago’s Adler Planetarium as well as writing and editing for The Darchives. He also loves observing for DES in Chile, where he has observed more than 30 nights.